PC Motherboard Form Factors Explained

Everything Smaller Also Fits!

The term Form Factor refers to a set of dimensional standards that assure compatibility between different parts made by various manufacturers. Non-proprietary PC motherboards and cases rely upon the decades-old ATX standard and its derivatives, which include everything from the gigantic Extended ATX to miniscule Mini-ITX parts. We’re using imperial measurements in the following table because that’s the actual system that was used (no rounding of numbers required).

| Current Motherboard Form Factors | |||||

| EATX | ATX | Micro-ATX | Mini-DTX | Mini-ITX | |

| ‘Width’ | 12.0 | 12.0 | 9.6 | 8.0 | 6.7 |

| Depth | 13.0 | 9.6 | 9.6 | 6.7 | 6.7 |

The term “Width” is based on the fact that most servers have horizontal motherboards. To avoid confusion for builders of tower systems, we refer to the distance from the front edge to the rear port panel as “depth”.

From ATX On Down

The ATX motherboards introduced in the 1990s soon replaced their Baby AT predecessors, due mostly to ATX’s inclusion of an I/O panel on the rear (for keyboard/mouse, USB, network and audio ports), and partly to its dedicated CPU mounting space. The earlier Baby AT boards often mounted the CPU beneath the leading edge of expansion cards, and that simply wouldn’t work when CPUs started needing their own cooling solutions!

A seven-slot motherboard is illustrated, but most manufacturers have recently replaced the upper card slot with an M.2 drive slot. It’s still an important location for comparing other form factors.

Micro ATX

Also called Micro-ATX (the hyphen doesn’t mean anything), these make up the oldest variation of ATX. Owing to its identical mounting depth, Micro-ATX motherboards can fit as much memory and as big a CPU cooler as their larger ATX siblings. Light gray outlines in the below photo illustrate how the larger ATX motherboard compares.

Micro-ATX is probably the most practical layout for performance-oriented machines that include only a single graphics card with an enormously-thick graphics cooler. Even though its three remaining slots would mostly be covered by those graphics coolers, corresponding cases provide room to mount those parts.

Mini ITX

Like Micro-ATX, Mini-ITX can be spelled with or without hyphenation. Originally designed exclusively to support low-power processors, cramped space around the CPU socket limits its ability to support more than two memory modules or oversized CPU voltage regulators. Most motherboard manufacturers have applied advanced designs to overcome those limitations in an effort to attract builders of portable gaming machines.

Notice that Mini-ITX uses the same four mounting locations surrounding the CPU as ATX: Smaller boards can always fit into larger cases, and one peculiarity of those portable gaming machines is that their so-called Mini-ITX cases usually…aren’t. Read on!

Dead Compact Form Factors

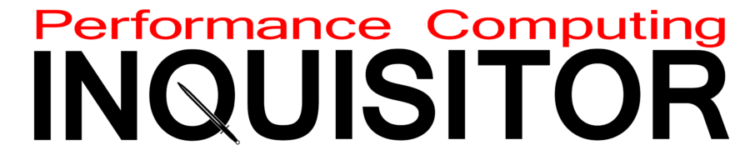

As mentioned above, most Mini-ITX gaming systems are built into case a bit larger than their designated form factor, such as DTX or Mini DTX.

DTX reduces Micro-ATX to two slots and cuts 1.6” from its width in the process. Since many compact gaming cases are designed to hold long graphics cards, quite a few of those could have fit these boards. With all of the ATX form factor’s 9.6″ of depth for CPU cooling and memory slots, it should have been the ideal compact performance form factor.

Mini-DTX resembles DTX shortened to Mini-ITX depth. This is the actual form factor present in most Mini-ITX gaming cases, since manufacturers saw the lack of DTX adoption as an opportunity to add a drive cage to the empty space in front of a Mini-ITX motherboard. Now that drive cages are falling out of favor, some manufacturers have began using that space to mount a power supply next to the graphics card.

By now you might be wondering “if all these cases are DTX or Mini-DTX, why are no motherboards available in this form factor?” The answer is that Mini-ITX was already established by the time DTX and Mini-DTX specifications were released. Too many builders were clueless regarding the advantages of DTX/Mini-DTX or its compatibility with the cases they already owned.

A popular form factor for OEMs of the Y2K era, FlexATX was a compacted alternative to Micro-ATX. Several current ‘Micro-ATX’-labeled motherboards are this small, and the case’s compatibility with Mini-ITX motherboards has kept a pathway open for those who like to put modern hardware into vintage enclosures.

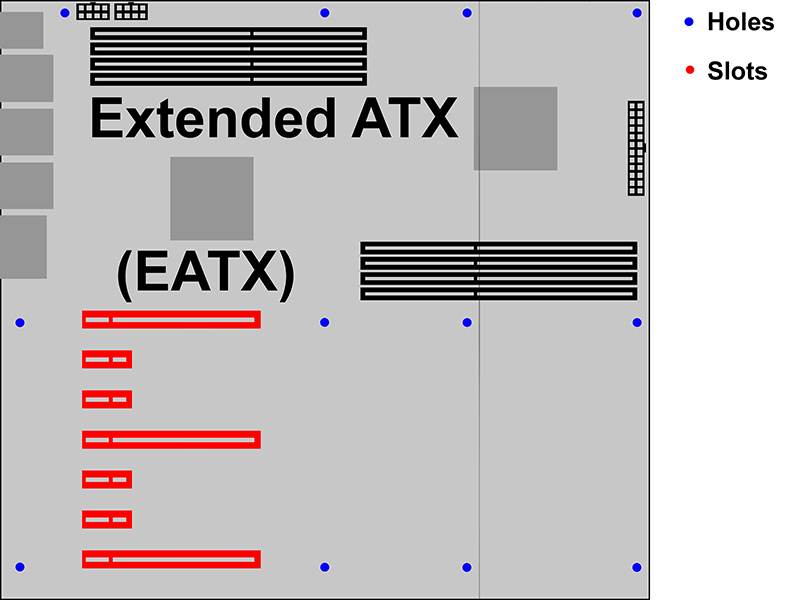

Going Large

Extended ATX (aka E-ATX or EATX) is the original “big-up” standard that allowed multi-processor configurations to fit into the same “width” (ie, the same tower height) as ATX. The 3.4″ of extended depth that made space for the extra CPU socket and memory slots required three additional mounting holes to support the front edge. Cases compatible with this specification should have three additional standoffs to support those mounting holes, but we’ll talk more about that in our next section.

XL-ATX was never standardized, but several motherboards of slightly different proportions were released under this name, and all compatible cases had enough space for a board at least 13.6” ‘wide’ and at least 10.6” deep. All available boards were somewhat short of this maximum.

Quad-SLI was the purpose of XL-ATX, and support for four double-slot cards is why the board was extended to eight slots. A bunch of cases still support these boards, even though hardly anyone uses four graphics cards in a gaming system. One remaining benefit of the oversized cases is that when an ATX motherboard has a graphics card slot at the bottom, the eighth slot of the case will provide room for the thick card’s extra ports and vents.

The Problem Of Limits

All of these motherboard widths and depths are dimensional maximums for the motherboard and dimensional minimums for the case. Because of that we see FlexATX-sized motherboards currently marketed as Micro ATX: Few builders recognize the term FlexATX, so that any manufacturers using that term would find no buyers in the larger Micro-ATX market. We’ve seen worse, such as 9”-deep “ATX” motherboards that didn’t quite reach the front three standoffs. Memory slots typically occupy the unsupported forward edges of those boards, and it’s quite possible to damage such boards while inserting memory modules.

Because form factors are dimensional maximums for the motherboard and dimensional minimums for the case, all ATX cases must be able to support all ATX motherboards and all XL-ATX cases must be able to support all XL-ATX motherboards. The problem is that many enthusiast-class ATX motherboards are actually 10.6” rather than 9.6” deep and, lacking any form factor in the middle, must be labeled either EATX or XL-ATX.

What are the implications of labeling a motherboard that’s only 10.6” (rather than 13″) deep as EATX? A dozen years ago when a site asked this editor to help select standardized equipment, I picked an XL-ATX case with over 11” of available motherboard mounting depth. A fellow editor from Germany said that it would not support his chosen motherboard. The fact that the selected 10.6″-deep motherboard was labeled EATX and the case wasn’t was all he needed to know. He flat-out refused to even look at any dimensional data: Labels were all he needed.

More recently, many case manufacturers have responded to the type of mindset just described by sticking EATX labels on cases that cannot support a 13”-deep motherboard, thereby violating the principle of form factors; that any case labeled EATX must support any EATX motherboard. Consequently, several other case manufacturers are now treating the EATX form factor as dead and instead using the industrial PC term “SSI-EEB” to describe the same 12” by 13” dimensions and motherboard mounting points. But in high-end consumer spaces EATX was the king. Long live the king.